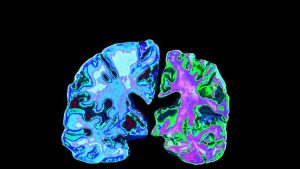

The fight to cure Alzheimer’s has been a long and arduous one for countless scientists dedicated to creating drugs that slow mental deterioration and extend quality of life for those afflicted. Currently there are a number of drugs, at various states of their clinical trial evolution, attempting to make their way down the chain to eventual FDA approval.

One of these drugs, a Biogen developed pill called aducanumab, recently became the first FDA-approved drug in 18 years for the treatment. The medication is a monoclonal antibody, administering clumps of amyloid beta, a sticky plaque compound that is believed to damage communication between brain cells and kill them. The drug is designed to remove plaque from the brain by triggering an immune response.

The first human clinical trial of the drug had promising results, with 22% slower mental deterioration for subjects who were administered the drug as compared to placebo groups. However, the second trial was not as conclusive, leading many critics to suggest an additional clinical study on aducanumab before it should be cleared for marketing.

The drug has many advocates, including patients, doctors, and groups like the Alzheimer's Association and UsAgainstAlzheimer’s. Though many of these advocates collectively acknowledge the flaws with the clinical trial results, the favorability of this drug’s approval lies in the research potential it opens in the industry after an 18-year stalemate in pharmaceutical progress.

Harvard Medical School is, on the other hand, looking to develop a treatment that utilizes the enzyme Pin1 to prevent neurodegeneration by converting a tau protein called cis P-tau to a trans conformation, meaning it can no longer disrupt the health of neurons that causes the formation of tau tangles, a signature of Alzheimer’s disease.

Unlike aducanumab, which had a shaky beginning before human trials, Harvard’s new antibody treatment is in early animal trials successfully showing better outcomes in spatial memory and motor memory in trials conducted on 13-month-old mice with diagnosed cognitive impairment.

The Harvard team suggests that this new form of antibody could recover cognitive abilities in mice and proves that a build-up of tau may not be as harmful as previously thought on the Alzheimer’s brain. The development of this drug could critically impact the way that this disease is handled in the future.